(HedgeCo.Net) In an industry that often equates scale with edge—more analysts, more data, more technology, more leverage—Lucida Capital is an uncomfortable counterexample. The Canada-based hedge fund is operated solely by Francis Lau, and yet it posted a 65% gain from April through the end of 2025 without using leverage, putting it among the country’s top performers and ahead of many far larger, better-resourced rivals.

This Bloomberg story matters for more than its novelty value. In a year when leverage across the hedge fund ecosystem has been pushing toward historic highs as managers compete for incremental returns, a standout, no-leverage performance forces investors to re-examine what actually drives alpha: structure, process, position sizing discipline, and the ability to exploit market micro-inefficiencies—often faster than large organizations can move.

This is not a claim that “one-person funds are the future,” or that leverage is inherently bad. Rather, Lucida Capital’s run offers a case study in how returns can be created when constraints are embraced: capacity limits, simplicity of decision-making, low overhead, and a willingness to be meaningfully different from benchmarks.

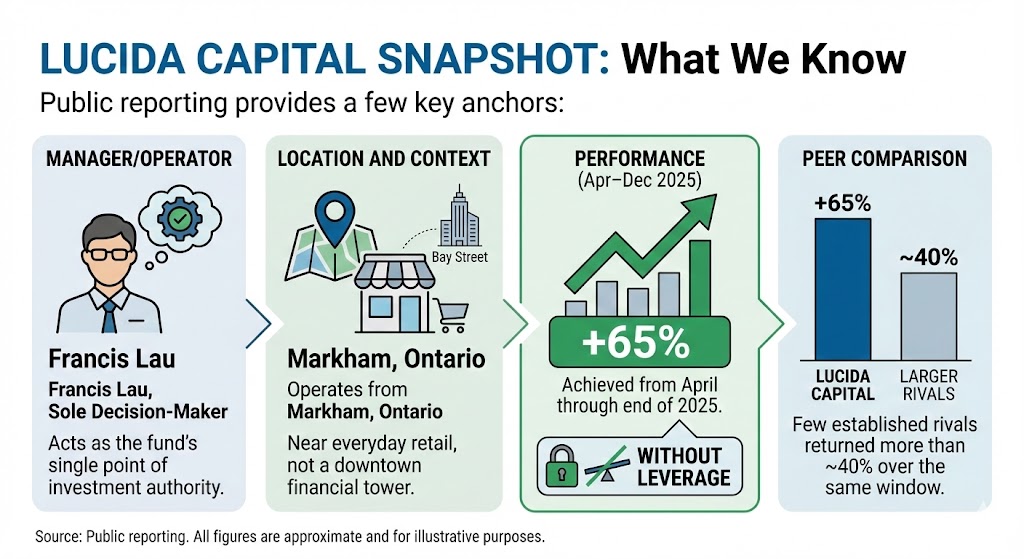

Public reporting provides a few key anchors:

- Manager/operator: Francis Lau, who acts as the fund’s sole decision-maker.

- Location and context: Lau operates away from Canada’s Bay Street financial core—reportedly from an office in Markham, Ontario, near everyday retail landmarks rather than a major downtown tower.

- Performance: +65% from April through the end of 2025, achieved without leverage.

- Peer comparison: Few larger, established rivals reportedly returned more than ~40% over the same window.

That’s enough to frame the discussion: a large return, over a defined period, produced without the most common mechanical accelerator (borrowing).

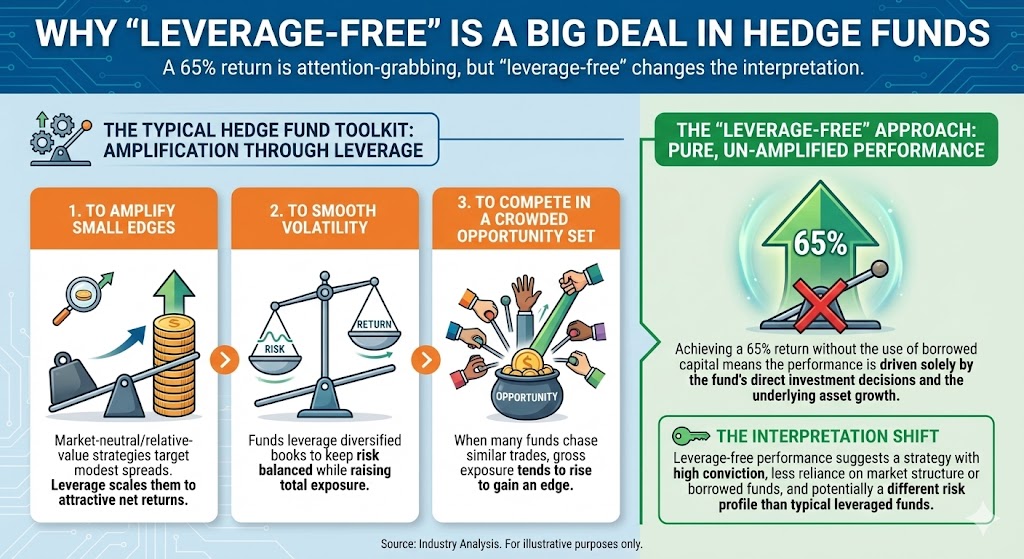

Leverage is often used in hedge funds for three broad reasons:

- To amplify small edges: Market-neutral and relative-value strategies may target modest spreads and scale them via leverage to reach attractive net returns.

- To smooth volatility: Some funds leverage diversified books, aiming to keep risk balanced while raising total exposure.

- To compete in a crowded opportunity set: When many funds chase similar trades, gross exposure tends to rise.

The tradeoff is straightforward: leverage can magnify returns, but it also magnifies mistakes, correlations, liquidity shocks, and the speed at which drawdowns become existential.

That’s why Lucida’s result stands out against the broader industry backdrop. Reuters has documented hedge fund leverage hovering near record levels in late 2025, driven by equity trading and AI-fueled market dynamics—conditions that can reward risk-taking until they don’t. In that environment, a no-leverage 65% run suggests that the driver was not “more exposure,” but “better exposure.”

The structural advantages of being a one-person hedge fund

The phrase “one-man hedge fund” tends to be used as a curiosity. For investors, it should instead be treated as a description of structure—with real pros and cons.

1) Speed as an edge

Large hedge funds rarely lack ideas. What they often lack is execution speed across committees, risk constraints, sector sleeves, and portfolio construction rules designed for stability. A single decision-maker can act quickly when a dislocation appears—especially in less trafficked mid-cap names, special situations, or fast-changing narratives.

2) Capacity and liquidity

Some of the best opportunities in public markets are simply too small for mega-funds. If a position can only absorb a few million dollars before prices move, the trade is irrelevant to a multi-billion-dollar platform—but meaningful to a smaller fund. If Lucida capitalized on these “small pond” inefficiencies, the return profile makes more sense.

3) Lower operational drag

With fewer layers, fewer mandates, and fewer internal “silos,” the portfolio can be constructed with coherence. Many large funds end up being a collection of sub-books whose correlations spike in stress. One PM can keep the risk thesis integrated.

4) A clean incentive loop

In bigger organizations, decision-making and consequences can be separated: an analyst pitches; a PM sizes; a risk committee trims; a senior partner overrides. In a one-person fund, feedback is immediate. That tends to sharpen process—assuming the manager is disciplined and self-critical.

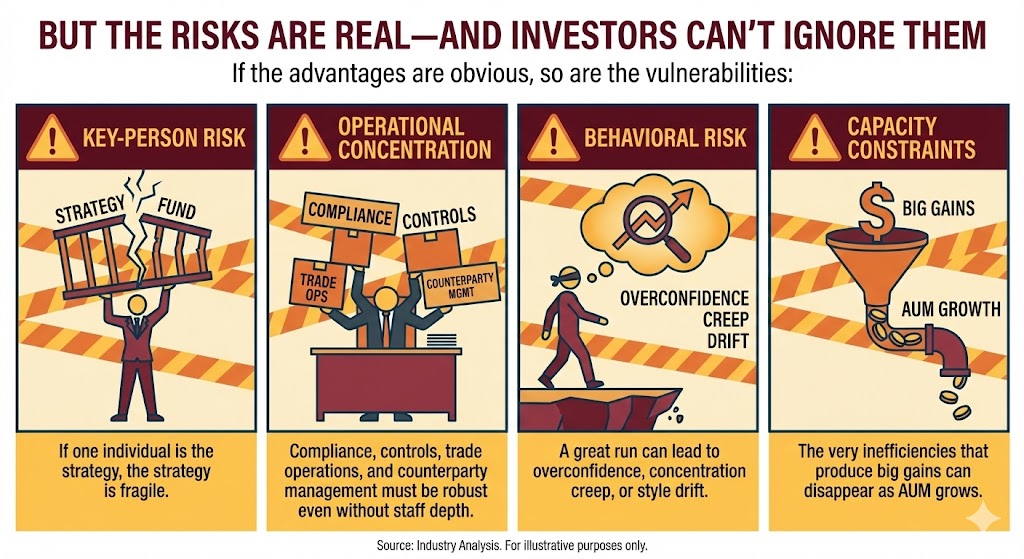

If the advantages are obvious, so are the vulnerabilities:

- Key-person risk: If one individual is the strategy, the strategy is fragile.

- Operational concentration: Compliance, controls, trade operations, and counterparty management must be robust even without staff depth.

- Behavioral risk: A great run can lead to overconfidence, concentration creep, or style drift.

- Capacity constraints: The very inefficiencies that produce big gains can disappear as AUM grows.

This is why sophisticated allocators treat a standout year not as proof, but as a prompt: How was it achieved, and can it be repeated?

How a no-leverage fund can generate a 65% run

Without access to Lucida’s full portfolio, any explanation must be framed as mechanisms rather than specific holdings. Still, there are clear pathways by which leverage-free returns can become unusually large:

1) Concentrated, high-conviction equity selection

A concentrated long book—especially in mid-caps—can outperform massively in a strong tape. If a manager catches a handful of idiosyncratic winners (re-rating stories, turnarounds, M&A catalysts), the compounding can be dramatic without borrowing.

2) Event-driven and catalyst-driven timing

Catalyst investing is often misunderstood as “guessing headlines.” In practice, it’s about identifying a timeline where the market is mispricing the probability distribution. If Lucida leaned into corporate actions, restructurings, or inflection points, returns can spike quickly—especially when the market’s attention is elsewhere.

3) Volatility as an input, not an enemy

A one-person fund can be structurally comfortable with volatility if its capital base is stable and its risk framework is tight. The ability to buy when forced sellers appear is often the difference between “good” and “great” years.

4) A disciplined downside framework

Here’s the quiet secret: the most explosive return years often come from not blowing up during drawdowns. If a manager keeps losses small, they preserve the ability to press when the odds are skewed. The arithmetic matters—avoiding a 20% drawdown means you don’t need a 25% recovery just to get back to even.

The 2025–2026 backdrop: a market that rewarded selectivity

Industry-wide, 2025 was a strong year for many hedge fund styles, helped by buoyant equities even amid volatility and policy uncertainty. Reuters reported hedge funds posting strong double-digit gains in 2025, with stock-picking strategies averaging in the mid-teens in some datasets—good results, but nowhere near Lucida’s pace.

That spread is important. When “the average fund” is up, it becomes easier for a top-decile manager to look like a genius, and harder to disentangle beta from alpha. Yet Lucida’s reported outperformance versus many large peers—while remaining unlevered—suggests something beyond simply riding the market.

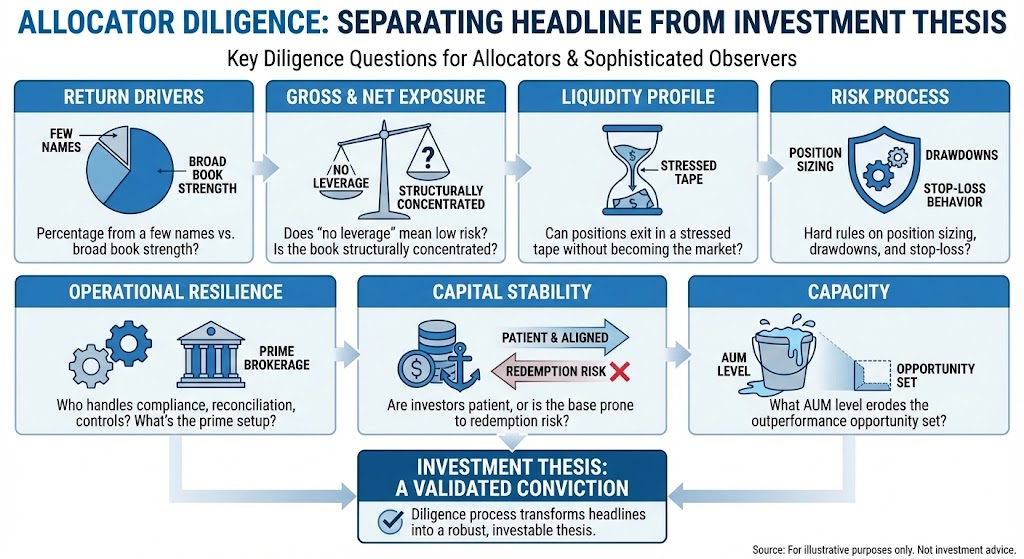

What allocators should ask before treating this as repeatable:

If you’re an allocator—or a sophisticated observer—here are the diligence questions that separate a headline from an investment thesis:

- Return drivers: What percentage came from a few names vs. broad book strength?

- Gross and net exposure: “No leverage” doesn’t automatically mean “low risk.” Was the book structurally concentrated?

- Liquidity profile: Could positions be exited in a stressed tape without becoming the market?

- Risk process: What are the hard rules on position sizing, drawdowns, and stop-loss behavior?

- Operational resilience: Who handles compliance, reconciliation, and controls? What’s the prime brokerage setup?

- Capital stability: Are investors patient and aligned, or is the capital base prone to redemption risk at the wrong time?

- Capacity: What AUM level begins to erode the opportunity set that produced the outperformance?

The broader takeaway: simplicity can still win

Lucida Capital’s run lands at an interesting moment for the hedge fund business model. The industry is increasingly bifurcated:

- At one end: mega-platforms with industrialized risk systems, large teams, and steady single-digit-to-low-teens targets.

- At the other: small, nimble funds that can exploit capacity-limited opportunities—often with higher volatility and more key-person risk.

In 2025, leverage in parts of the hedge fund ecosystem has been elevated, raising long-term questions about crowding and unwind risk. Against that backdrop, an unlevered 65% surge is a reminder that outsized outcomes still exist in public markets when a manager can move quickly, stay focused, and avoid the institutional friction that sometimes dilutes edge.

But the conclusion isn’t “copy this.” The conclusion is more nuanced: structure shapes returns. A one-person fund can be extraordinarily efficient—until it isn’t. A no-leverage approach can be a signal of discipline—until concentration becomes the hidden leverage. A great year can reflect repeatable process—until the market regime shifts.

For now, the cleanest interpretation of Lucida’s performance is also the most practical: in a world where many funds increasingly rely on borrowed exposure to compete, Lucida’s 65% run shows that selection, timing, and risk control can still do the heavy lifting—no mechanical amplifiers required.