(HedgeCo.Net) For more than a decade, private credit was Wall Street’s cleanest growth story: a vast pool of institutional capital stepping into the space banks retreated from after the financial crisis, lending directly to middle-market companies and private equity–backed issuers. The pitch was simple and compelling—floating-rate coupons, tighter lender control, and less mark-to-market volatility than public credit.

Now, the mood has shifted. As the rate cycle turns and refinancing windows narrow, investors, banks, and regulators are asking a harder question: what happens if private credit faces a true downcycle—one that tests underwriting, valuation practices, liquidity assumptions, and the web of financing lines that connects private lenders to the traditional banking system?

This isn’t a prediction of imminent collapse. But it is a recognition that private credit has grown large enough—and intertwined enough with the broader financial system—that a meaningful deterioration in credit outcomes could travel farther and faster than many market participants expect.

Why “meltdown” is suddenly part of the conversation

Private credit’s risk profile is often misunderstood because it doesn’t trade on an exchange and rarely reprices daily. That opacity has been a feature, not a bug. It reduced forced selling and helped investors look through volatility.

But opacity cuts both ways. When stress rises, the absence of transparent price discovery can delay recognition of problems, encourage “extend-and-pretend” restructurings, and compress the time available to respond when losses can no longer be deferred.

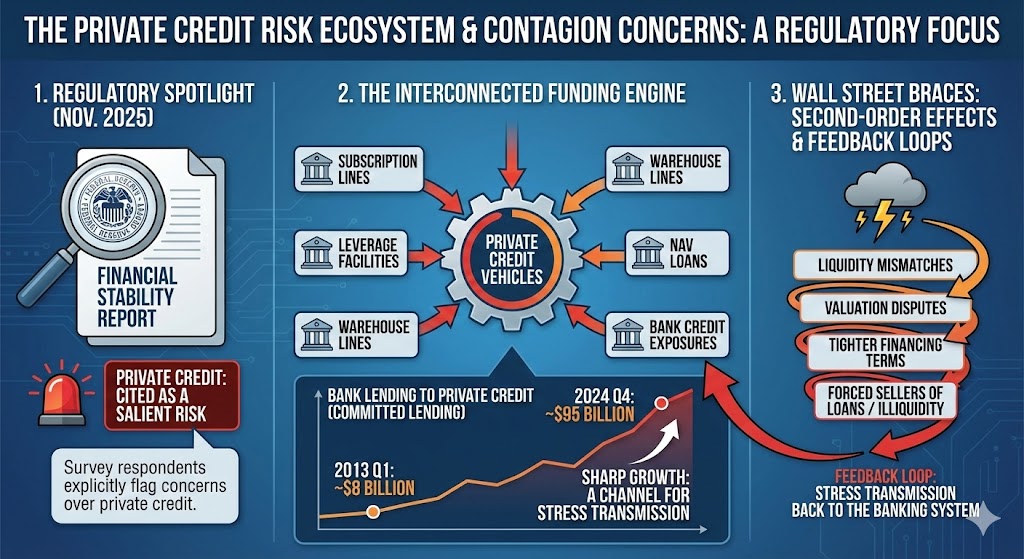

Regulators have increasingly flagged this category of concern. In the Federal Reserve’s Financial Stability Report (Nov. 2025), survey respondents explicitly cited concerns over private credit among salient risks to financial stability.

Meanwhile, private credit is not isolated. It has become funded and enabled by other parts of Wall Street—subscription lines, leverage facilities, warehouse lines, NAV loans, and bank credit exposures to private credit vehicles. A 2025 Federal Reserve analysis documented that banks’ committed lending to private credit vehicles grew sharply from roughly $8 billion (2013 Q1) to around $95 billion (2024 Q4), highlighting a channel through which stress could transmit back into the banking system.

When people say “Wall Street braces,” they’re bracing for second-order effects: not just defaults, but liquidity mismatches, valuation disputes, tighter financing terms, and the feedback loop that can form when lenders become forced sellers of loans—or when they can’t sell at all.

The vulnerability stack: what could actually go wrong

A “meltdown” scenario in private credit would likely be less about one dramatic blowup and more about a stacked sequence of pressures that reinforce each other.

1) Refinancing pressure meets slower growth

Private credit borrowers are typically leveraged companies, many owned by private equity sponsors. They can handle leverage when EBITDA rises and capital markets cooperate. They struggle when growth slows and refinancing terms worsen simultaneously.

Even if benchmark rates drift down from peaks, the damage from the hiking cycle can persist through:

- higher all-in interest burden locked in via spreads,

- shorter maturities, and

- tighter lender control that limits flexibility.

S&P Global has also emphasized the way rate dynamics can change the math for borrowers and lenders, noting that benchmark rates (like SOFR) moved meaningfully from their highs, reshaping interest expense and refinancing conditions going into 2026.

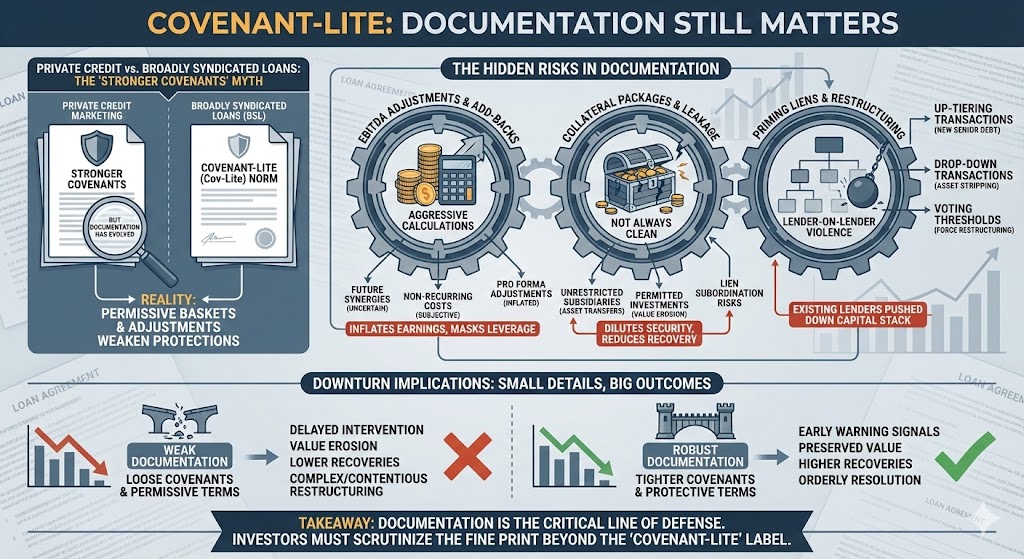

2) Covenant-lite isn’t “no covenants”—but documentation still matters

Private credit often markets itself as “stronger covenants than broadly syndicated loans.” Sometimes that’s true. But documentation has evolved. Add-backs, EBITDA adjustments, and permissive baskets can quietly weaken lender protections.

In a downturn, outcomes can hinge on small details:

- whether EBITDA is calculated conservatively,

- whether collateral packages are clean,

- whether priming liens are possible,

- and how quickly lenders can force a restructuring.

If a wave of borrowers drifts into covenant breaches at once, lenders may face a choice between rapid restructurings (realizing losses) and maturity extensions (delaying recognition). Neither is painless.

3) “Smoother valuations” can become a trap

Private credit’s reported volatility has historically looked modest relative to public high yield. That’s partly due to structure (senior secured loans, floating rate), but also because valuations are appraised rather than continuously traded.

In benign periods, this reduces noise. Under stress, it can create:

- lagged markdowns that hit fund NAVs after problems are widely known,

- disagreements between GPs and LPs about marks, and

- complications for any fund using NAV-based leverage.

This becomes crucial if funds rely on borrowing where collateral value is tied to marks.

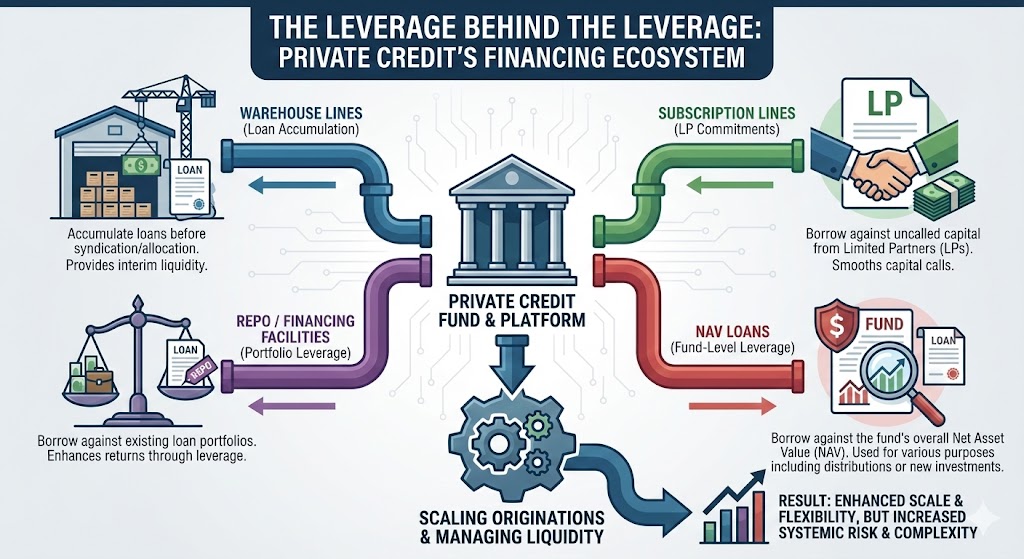

4) The leverage behind the leverage: lines, warehouses, and NAV loans

Private credit funds and platforms increasingly use financing to scale originations and manage liquidity:

- warehouse lines to accumulate loans before syndicating or allocating to vehicles,

- subscription lines against LP commitments,

- repo/financing facilities against portfolios, and

- NAV loans at the fund level.

These structures are not inherently bad. But in a stress scenario they can create margin-like dynamics: lenders tighten terms, haircuts increase, covenants bite, and borrowers are forced to delever at unfavorable prices.

This is why regulators and risk managers focus on the system linkages. The Fed’s findings on bank lending commitments to private credit vehicles underscore that these connections have expanded materially.

5) Liquidity and the rise of semi-liquid products

One of the biggest structural shifts is the move into private wealth channels. As private credit expands beyond institutions into interval funds, tender-offer funds, and other semi-liquid wrappers, the industry has to manage redemption expectations against inherently illiquid assets.

If redemptions rise during a drawdown, funds may:

- gate withdrawals,

- sell more liquid positions first (quality drift), or

- rely more heavily on financing—exactly when financing may tighten.

The result can be reputational damage that becomes a fundraising headwind—turning a credit problem into a business model problem.

What the “meltdown” would look like in markets

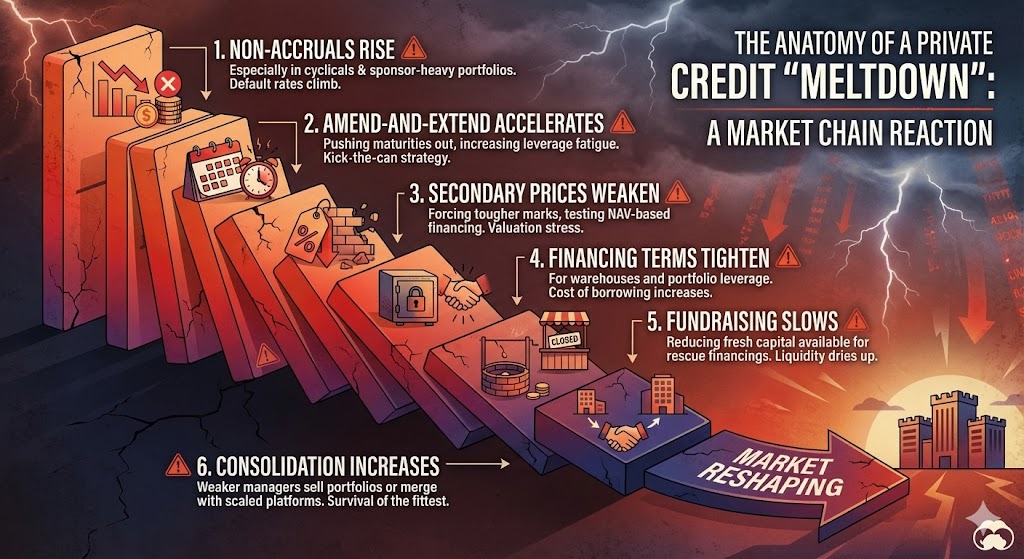

A private credit downturn would likely surface in a recognizable pattern:

- Non-accruals rise (especially in cyclicals and sponsor-heavy portfolios).

- Amend-and-extend accelerates, pushing maturities out but increasing leverage fatigue.

- Secondary prices weaken, forcing tougher marks and testing NAV-based financing.

- Financing terms tighten for warehouses and portfolio leverage.

- Fundraising slows, reducing fresh capital available for rescue financings.

- Consolidation increases, as weaker managers sell portfolios or merge with scaled platforms.

Wall Street’s concern isn’t simply credit losses—it’s the possibility that credit losses interact with funding channels and investor behavior in ways that amplify stress.

The counterargument: why many believe fears are overblown

It’s equally important to acknowledge the other side: major private credit platforms argue that fundamentals remain manageable, and that the “meltdown” narrative is often headline-driven rather than data-driven.

Large managers point to:

- senior secured positioning,

- sponsor support through equity cures and rescue capital, and

- active portfolio management that can intervene earlier than public-market lenders.

Some market commentary from major platforms has emphasized that credit conditions and defaults do not currently resemble a systemic crisis environment.

There’s also a structural argument: private credit funds generally have less run risk than banks because their capital is largely locked up, and they don’t rely on deposit funding. Research from the Boston Fed has noted that if private credit growth reflects a shift away from banks, it may reduce certain forms of instability associated with bank leverage and run dynamics.

In other words, the system may absorb stress differently than in 2008—more slowly, more privately, and with different spillover channels.

What to watch: the real early-warning indicators

If you want to gauge whether “brace for impact” is becoming reality, focus less on narratives and more on measurable signals:

- Non-accrual rates in BDCs and comparable portfolios (often the clearest public window into private credit stress).

- Private credit secondary pricing and the bid-ask spread for whole loans and LP stakes.

- Amend-and-extend volume and the ratio of restructurings to true refinancings.

- Warehouse and fund-level financing terms (haircuts, spreads, covenants).

- Sponsor behavior (equity cures, rescue financings, willingness to support marginal credits).

- Sector concentration (software, services, healthcare services can be resilient—some cyclicals are not).

- Bank exposure disclosure (commitments, utilization, and the quality of counterparties), especially given the documented growth in bank lending to private credit vehicles.

The bottom line

Wall Street isn’t bracing for private credit because it expects every loan book to implode. It’s bracing because the asset class has matured into a pillar of modern financing—large enough that a normal credit cycle could feel abnormal if valuations, liquidity structures, and financing channels are tested simultaneously.

A true “meltdown” would require multiple things to break at once: sustained earnings pressure, refinancing constraints, rising non-accruals, tightening leverage facilities, and investor pushback on marks and liquidity. That’s not the base case for many large managers. But it’s no longer an unthinkable tail risk either—especially as regulators explicitly track private credit as part of the financial stability perimeter.